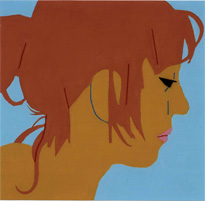

Roughly 30 years ago,I used to look forward to getting Dad to make spontaneous drawings of people or characters, in some (not so big) part because I knew he enjoyed it, but also because I could relate to the way the lines curved, or didn’t, as he made each shape, and because I knew that when something chopped itself off abruptly, it was meant to be abrupt. That same definition is at work here. I’ve kept abreast of the work all my life, of course, watching surreal landscapes progress into not-so-surreal landscapes; into intense close portraits of individuals; then back to more restive landscapes; then – wham! – into acrylic politicized work; and then, gradually, into alarming, dynamic pictures from commercial life (images of Shakira, Pink, and others on Manhattan walls); and then this, the Subway Series. These people….are undying components of human life, each one a separate keystone in a separate arch for a separate passageway in City Hall. They don’t speak because stones don’t speak.

Max Winter, 2005

The thing I admire most about my father’s work is its emotional reasons for being the way it is at any given point. He abandoned the surrealistic, introspective approach because he had to, in order not to lose his mind. And before he abandoned the early approach, he had to do it, regardless of how time-consuming it was. It was tied into a profound personal need; it was tied into who he was as a person. In an age when artists adopt a certain style because it’s hip, or keep doing the same old style over and over and over because their gallery dealers tell them they must or because their inner lives are stagnant, my father has stayed true to himself in the most essential sense of that expression: He has stayed open to the changes that naturally happen through the course of a life, and he has recorded and processed those changes in his work.

Jonah Winter, 2005